The Habit of Creating

Religion was not kind to me as a child.

I say that plainly, without drama, because the details matter less than the outcome. What stayed with me was not belief, but a sense of wonder around the human instincts to mark time and make meaning, even within imperfect or painful structures.

Despite the harm, I found beauty in rituals, ceremony, shared meals and seasonal rhythms. I found solace in the quiet comfort of doing familiar things like lighting candles, observing holidays, singing songs, and making objects with care. These small, repeated acts offered a sense of grounding amid chaos. They created order where none was guaranteed.

I didn’t have language for it then, but I was already learning something essential: meaning does not require a reason, or belief. Meaning requires attention.

Creation as a Way of Being

That early understanding returns to me now when I think about creativity.

In The Creative Act, Rick Rubin describes the creator not as someone who produces, but as someone who receives. A vessel, or a conduit. Someone attentive enough to notice what is already present and willing enough to let it move through them into form. Rubin’s framing articulates a truth that resonates deeply with my lived experience. For me, creating has never felt like forcing or coercing something into existence; it feels more like participation, like giving form to something that already exists.

When creation is present in my life, I feel more awake and responsive to the world around me. In its absence, what I miss is not productivity or output, but the sensation of being in conversation with life itself.

Creation, for me, is one of the most reliable ways to feel alive.

Stagnation Is Not Failure

Most of us don’t stop creating because we stop caring. We stop because life intervenes. Work might expand beyond its borders. Sometimes bodies need healing. Routines shift, energy thins, and seasons of transition narrow our focus.

I’ve lived through long stretches where my tools were nearby but untouched. The desire to make still existed, albeit dulled by exhaustion, injury, or the work of rebuilding a life. During those times, what disappeared was not identity, ability, or desire, but connection.

Stagnation is not failure; it’s disconnection. And reconnection rarely happens through force.

Why Habit Matters

This is where habit becomes essential, not as discipline or productivity but as care.

In Atomic Habits, James Clear writes about how meaningful change is rarely the result of dramatic action. Instead, it grows from small, repeated behaviors that make it easier to return to what matters. Habit, in this sense, is not about motivation but design.

In an example of habit stacking or bundling, I placed a small Turkish drop spindle beside my couch near my favorite window. Now, instead of doom scrolling on my phone over morning coffee, I listen to audiobooks while spinning early 20th century Austrian dowry flax into linen yarn. Curious? Check out Berta’s Flachs

When I think about the habit of creating, I think less about what I produce and more about what I protect; habit keeps the channel open. Habit reduces friction and makes space for the creative act.

Stephen King tells us the muse isn’t susceptible to creative fluttering. “Your job is to make sure the muse knows where you're going to be every day from nine 'til noon. or seven 'til three. If he does know, I assure you that sooner or later he'll start showing up.”

Here are the principles that feel most relevant to the habit of creative life right now:

Environment matters more than willpower.

I recently set up my studio in my tiny apartment. Visible tools, a cleared surface, a space that quietly signals welcome—these are not simply aesthetic decisions; they make returning easier.Small acts are sufficient.

Touching the materials counts. Sitting with the tools counts. Five minutes of attention is often enough to reopen the channel.Identity precedes outcome.

The goal is not to finish or perform, but to reinforce the truth of who you are becoming. Each small act becomes a bid for participation.Incremental change compounds.

One moment of attention changes very little. Repeated moments change how we inhabit our lives.

All 58 x 80 inches of my tiny studio as seen from my bed. Sunlight spills through the third-floor window, glinting off the loom that waits folded beside it. A downtown main street sounds from below, while the river beyond gives way to the mountains. The view alone makes this little corner feel like an artist’s loft, though the space itself is closer to a well-organized cupboard.

Habit does not manufacture joy or make us the creative vessels we already are. It simply keeps the door unlocked and tells your muse when and where to find you.

The Importance of Influence

None of us returns to creation alone.

After a major period of upheaval and transition in my life, I recently found myself feeling slightly more rooted, tentatively established, and wholly disconnected from my creative self. It took an insistent new artist friend in my adopted community to help me recognize my rut and urge me back into the act of making. He shared how one of his friends, another artist, has helped him reconnect during challenging times. We need these reminders sometimes, that we belong to a greater community, whether or not we’re feeling it.

Creators reach for one another constantly, across disciplines and distances. Sometimes that reaching takes the form of a book, a tool, or a sentence that stays with you longer than expected.

Sometimes it’s as simple and grounding as an invitation (repeatedly, for the introverts) when you are still finding your footing. These moments and the calls to “join us” matter because they hold both memory and space for us; they remind us of who we are and where we belong when we have temporarily lost contact with that knowledge.

Rows of colorful thrifted wool yarns, thriving greenery, favorite tools, and my trusty Anker speaker make for an inviting space to reconnect with the creative habit. Framed art by Matt Sesow

Preparation Is Participation

I’ve recently made some small items, mostly to familiarize myself: knitted mittens for the first snowfall, a handful of woven squares. But right now my creative life mostly looks like preparation: a small, intentional space with tools and materials within reach, arranged not for productivity but for invitation.

This preparation is not a delay. It is part of the process, as is the mental work of imagining a woven textile series, or working out the lift plan for a new weaving pattern on paper or, you know, in your head at three o’clock in the morning.

Designing a space that welcomes creativity is an act of trust. It says: I am making room. I am available. I am open to the process returning in its own time.

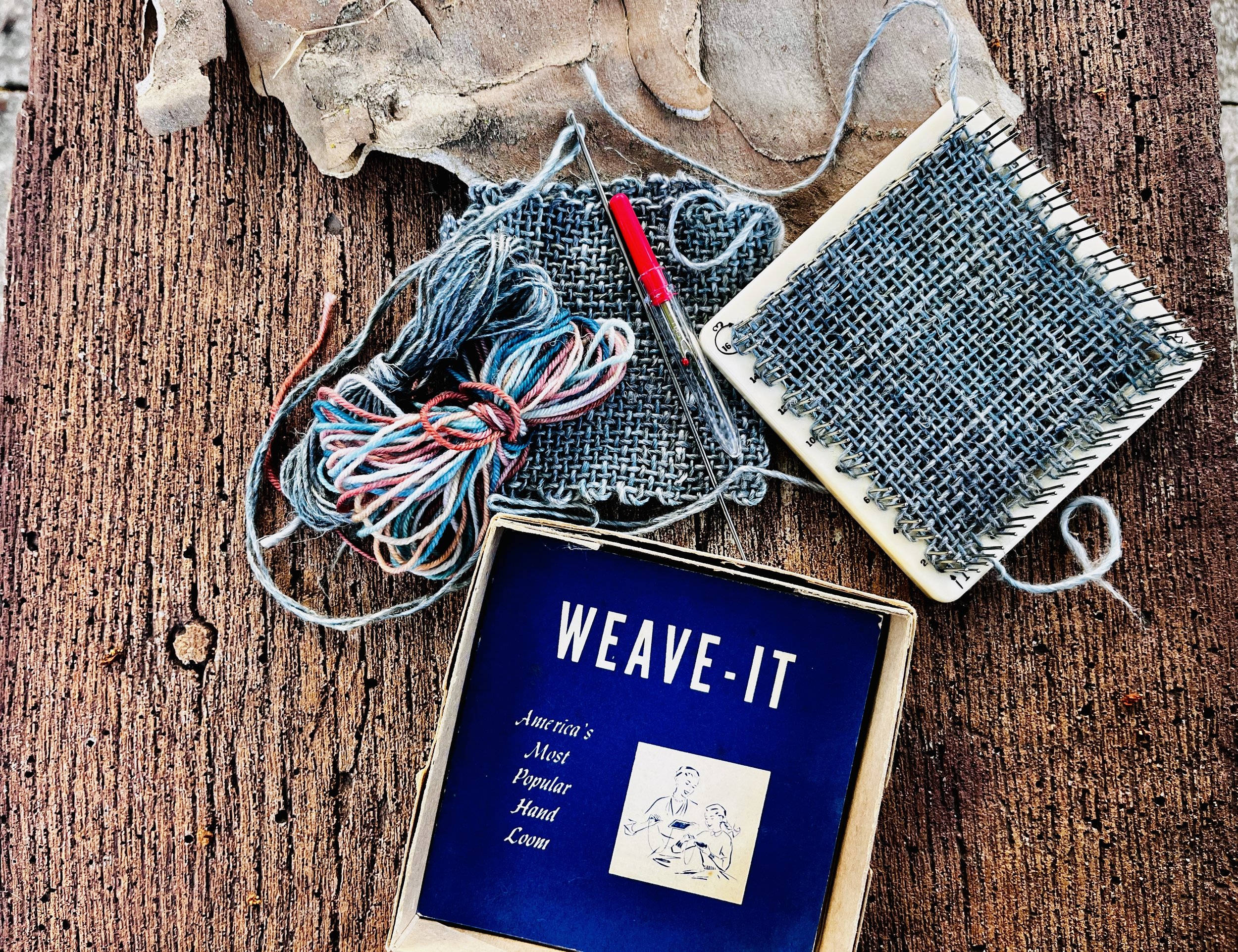

Weaving a small square on a vintage Weave-It pin loom, late autumn 2024 in Williamsport, PA. (See my note below.)

Creation Belongs to Everyone

It matters to mention that not all creators are artists.

Creation belongs to anyone who gives shape to something in a new or fresh way. Maybe it’s a home-cooked meal, a solution to a problem, a grounding ritual, or a way through difficulty. Creativity is not a category or a credential but a way of engaging with the world attentively.

The habit of creating is not about protecting an identity, but about protecting a relationship with curiosity, with sensation, and with joy.

Life Is the Special Occasion

This essay is being written during a season when many people are marking holidays. These moments of gathering, giving, and ceremony matter. But importantly, they are not the only times joy is allowed to surface.

One of the quiet lessons of my life has been this: joy does not require permission. It does not need a calendar date or a sanctioned reason to exist. The act of making—of noticing, shaping, and offering—is already a form of celebration.

Even in the chaotic religious setting of my childhood, I found peace in small acts done with care. In the ordinary made meaningful through attention.

I still do.

The habit of creating is, in part, the practice of remembering that life itself is the occasion. Being alive is reason enough to participate.

A Note on Pin Looms & Early Core Memory

Weave-It pin loom kit, thrifted for $3 in Lancaster, PA.

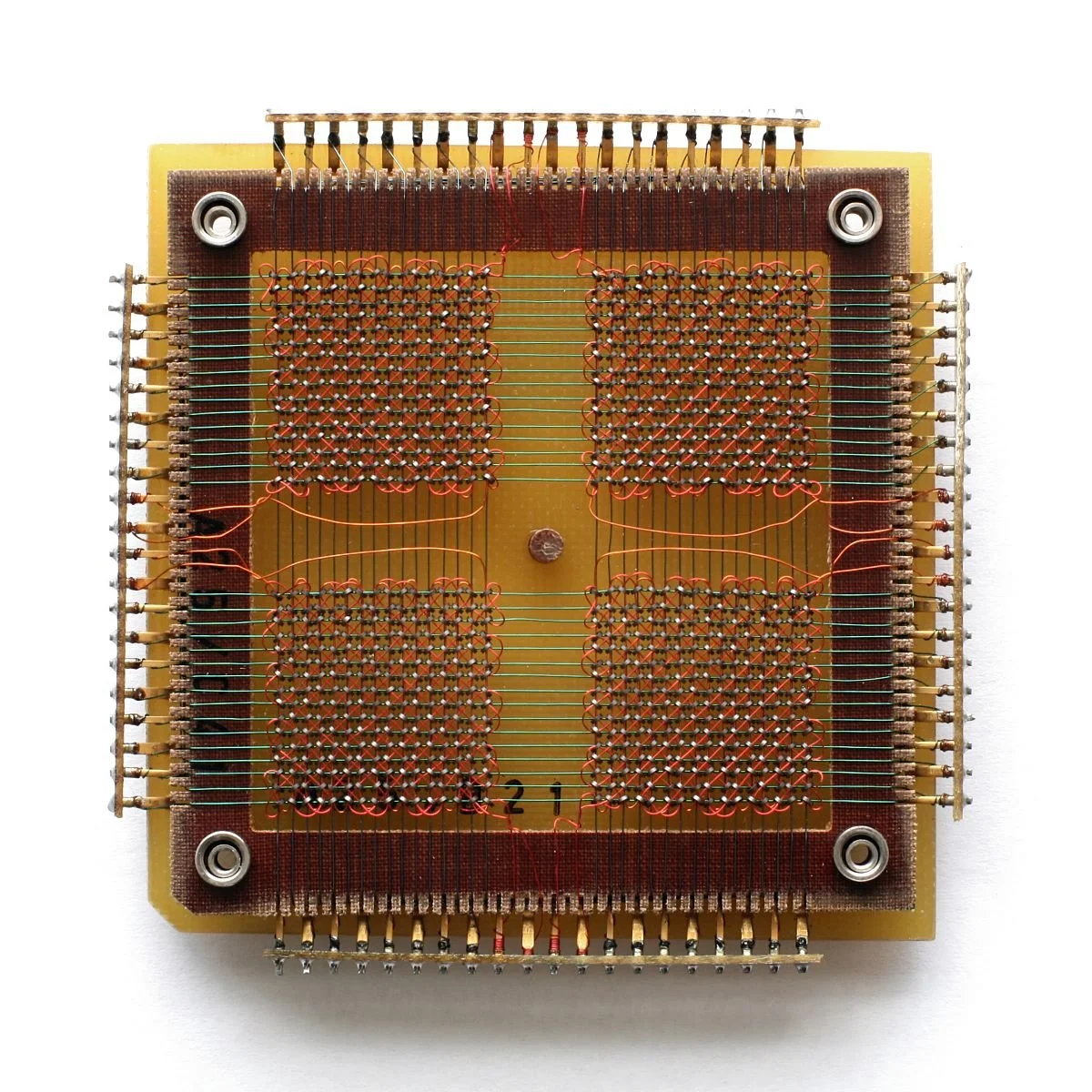

Handwoven core memory. Image: Konstantin Lanzet/Wikimedia Commons

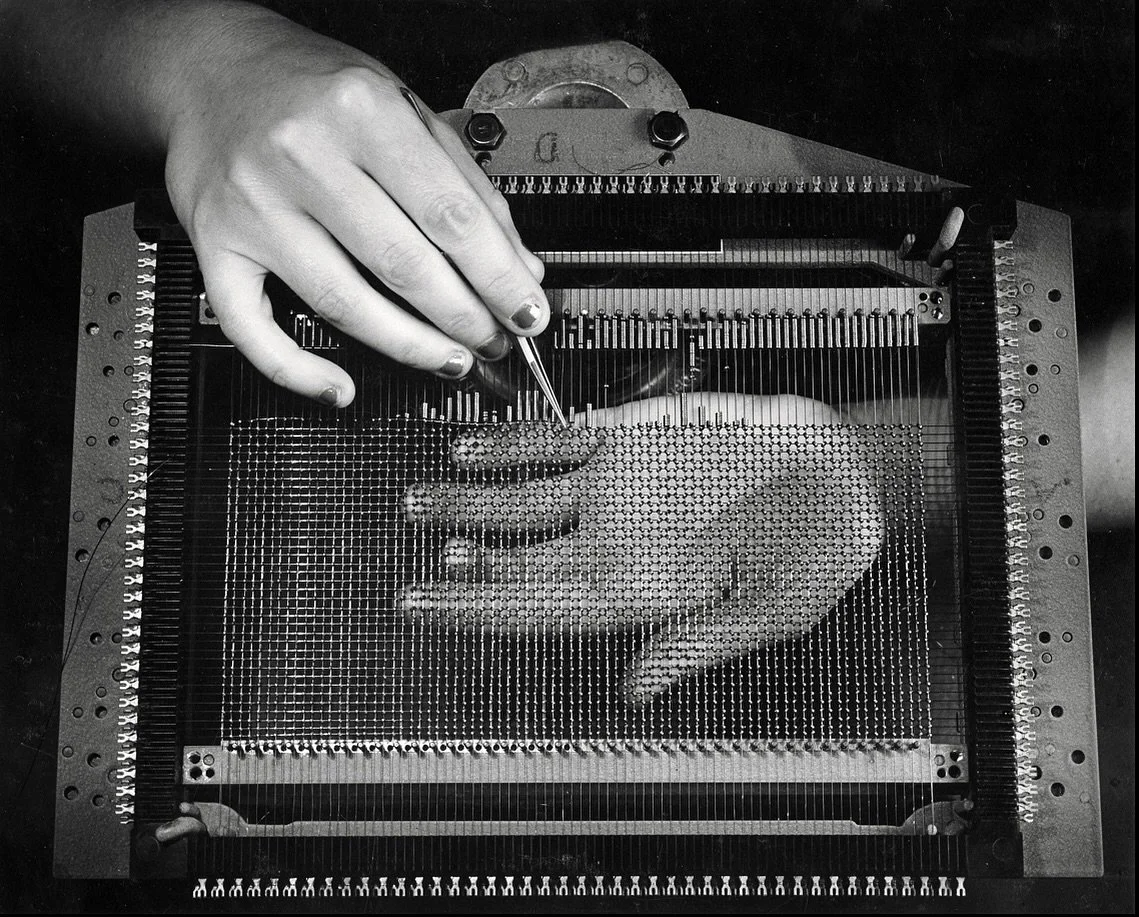

In the post titled From Jacquard to GPUs: The Textile Origins of Computing, I wrote about Raytheon’s Little Old Ladies (AKA LOLs) who literally wove early core memory boards for computing.

When I thrifted my little pin loom, I couldn’t help but notice the resemblance and feel a sense of community.

‘Hands weaving magnetic-core memory, IBM, Poughkeepsie, New York,’ 1956. Photograph by Ansel Adams